To Elizabeth Eckford, the Little Rock Nine, Linda Brown, Nikki & Nettie Hunt

Dear Elizabeth:

Dear Thelma. Dear Gloria. Dear Jefferson. Dear Melba, and Terrence. Dear Ernest, Carlotta and Minnijean. (Dear Daisy, too. Since but for you the Nine would not have made it.)

And I mustn’t ever, ever, forgot Dear Linda, whose father made a name for her by going to court to secure a decent education for her and her little sister Cheryl.

Dear Nettie and Nikki too, just because:

I’m so sorry.

No doubt you have like perhaps Black person -- indeed, every right thinking person -- in America been particularly reflective since Thursday at around 11:30 AM Eastern Standard Time. But where those of us who are strangers to the moment in time that was the unanimous Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education declaring segregated education inherently unequal on May 18, 1954 have the luxury (created by the gauzy lens of history) of reflecting on this past week's decision in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School Dist. #1, which declared that voluntary integration plans were inherently discriminatory against white students who could not have their choice of schools , you lived in the moment. Brown, and all that it signified to you for your individual educational goals at the time it was decided, was your moment in history.

And this week, you heard the highest court in the land say that despite 53 years of jurisprudence confirming that our national understanding of Brown's meaning -- that separate education is inherently unequal -- it really meant something else all along.

I suspect that you, like most, were surprised that Brown itself was at stake in Parents Involved and Meredith, and that it fell in all but name only. I admit that I was not. I wasn’t sure I believed it, when the decision actually came out; but I had the benefit of hearing quite early on -- as some of my friends were amici -- that the school districts received an extremely hostile reception at oral argument and, thus, knew which way the wind was likely to blow with this Court. But the official questions presented to the Supreme Court by the litigants in Parents Involved (and the case which was consolidated with it, Meredith v. Jefferson Cty. Board of Schools) made clear that it was the very concept of racial segregation that was again at issue, and that the Court must decide whether such segregation was constitutionally protected so long as it was the result of the government, but private citizen conduct (in housing choices) instead. That was not the advance billing either case was given, of course, but a simple glance at the Questions Presented themselves belie any other interpretation.

This is what happens when a nation is not paying attention, I guess. And probably explains why even though the most significant Supreme Court decision in the last 50 years has laid down for its final descent into death with what seems nary a whimper, let alone a heartfelt national hue and cry. Right now, there is an almost conspiratorial silence. The editorials have been tentative, and almost all of the few that have spoken at all, have refrained from rage, focusing instead on the ephemeral hope of an opinion by Justice Kennedy that has less precedential weight than the paper his clerks printed it out on. The blogs are almost silent - a single day in which there was notice, then it was back to political business as usual. It's as if nobody knows quite what to say. Perhaps it is because nobody really believed it would happen, the ending of Brown as viable precedent on the question of what racial equality in America really demands from us.

But I know what to say. Which is "I'm sorry." On behalf of our country. It would have been one thing for the Court to have decided that Brown was incorrectly decided 53 years ago. It is decidedly another for the Court to say that Brown was decided to protect the rights of white folks who made clear that the last concern they had on this earth was whether any child might be harmed by segregation if they couldn't have their way. Or their parents' way (since, of course, it is the parents and not the children who are the true actors in our nation's education dramas when it comes to race.)

Yet that is precisely what the Court did say, in so many (nearly 100 pages of) words. So I’m sorry. I'm sorry not just because you might feel that your courage facing the amoral expression of white segregationist fury just for trying to get an education was all for nothing. But I'm also sorry because despite your having fought the good fight for all of us, all of us must now confront the meaning, such as it is, in this week’s Supreme Court decision eviscerating the spirit of Brown v. Board of Education -- cynically through the words of Brown itself in Parents Involved.

I'm also sorry because in the end, when Parents Involved was decided on Thursday you were all instantly reduced to pawns in an unrealistic integrationist dream that finally died at age of 53, stabbed fatally through the heart by the families of (1) a little boy in Louisville, Kentucky whose mother thought his entire childhood would be ruined if he had to ride the school bus for 45 minutes a day for a single school year – until new school assignments were made in first grade – even though she enrolled him in school months too late for him to have the space available in his normally-assigned school close to home; and (2) an already-academically successful white teen in Seattle, Washington whose mother was convinced that his mild ADD and dyslexia diagnoses were so disadvantaging that he simply must overcompensate by taking a a spot in a distinguished biotechnology program to make up for it.

So in the end, your moral conviction allowed you to be played, as we were all played, into believing that somehow, the very example of your bravery and pride and dignity would permanently change the soul of a white nation, transforming it from the oasis of anti-Black hate it has been for 400 years into a nation where we would all sit and stand side by side with you, and your cultural heirs, in the classrooms of this nation where our citizens and citizenship are shaped (which we all know is the true purpose of education (as Eleanor Roosevelt said the Archbishop of York once told a group of headmasters.) I'm especially sorry for that.

If all that I wanted to say to you was "I'm sorry", I could have done that in far less words, no doubt. But that's not all I wanted to say to you, and the memories of your faces through your time of struggle and, ultimately, peaceful joy at what you thought was finally America doing right by us as Black people. What I wanted to say to you is that the old folks' saying that "Every Cloud Has a Silver Lining" is something we should remember. I wanted to share that good news with you, and let you know that no matter what anyone says, or thinks, or writes about the loss of Brown v. Board of Education and the end of that era, your original dreams as Black citizens of this country, and what you really fought for in Brown and in integrating Central High School (and as a mother explaining to her 3 1/2 year old baby on the steps of the Supreme Court that she was finally free, in the case of you, Nettie), did not die this week, no matter how disquieting the loss of Brown may feel (as it does to me; as if I am naked, or on a bad high, or perhaps a bit of both somehow....) In many ways, all of your hopes and dreams and our hopes and dreams as Black people were actually reborn from their death in Parents Involved-- like the Phoenix. They were given new life, in many ways, in the emotionally cleansing rhetorical fire that was Justice John Roberts' ugly manipulation and misuse of history and historical intent of the Fourteenth Amendment - and Brown itself to roll back the hands of time in Parents Involved. We could see them because, at long last, the rose-colored glasses were knocked off the nation's face. Particularly those we as Black people were wearing, individually and collectively. At least, I certainly hope so.

Since, of course, your fight was never about integration.

Please don't get mad at me for wasting your time telling you you all what you already know, which is that the point of Brown, and the goals of the attorneys like the late Justice Thurgood Marshall, and his mentor Charles Hamilton Houston, who systematically brought the desegregation cases before the courts over a more than a decade, piecing together precedents like a well-crafted quilt until they culminated in the facts and jurisprudence faced by the Supreme Court Brown, was never about anyone's desire for integration with white folks. Your , and their, actions were, instead, to further your personal and our collective goals as Black people seeking educational fairness and equality from the nation we built with our slave labor, not the nation's need to sing Kumbaya and pretend that its hundreds' year racist legacy as our slavemasters, oppressors and internal colonizers was actually behind us with no hard work at all. (This country's majority eschews the hard work of anti-racism, as I'm sure you well know. Indeed, they are so convinced that they are almost there at the promised land of "Racism is Over" that many have thrown their heart and soul into trying to elect a Black man (or 1/2 black - some folks are testy about calling him Black since he's mixed) President -- even as they do not deny that part of his appeal may be to guilt ridden and guilt fatigued white voters who will feel that, if he wins, he has "proven" that racism is dead in America.

Go figure. If only it was that easy, right? Oh well, at least they aren't trying to run Uncle Clarence, Lawn Jockey for the Right>

(who suddenly, in Parents Involved suggested in concurrence that was just trying to help by voting to reinterpret Brown; indeed, he articulated as close to Black nationalist concerns as he has come in decades -- most people don't remember, but I know that you do -- arguing that it was not in our people's best interest to rely on those pesky and unconstitutional desegregation commands to protect our collective rights or to eschew going to our own separate schools as we did quite successfully in our history, and that we should take care of our own needs instead of trusting white people not to up and change their minds again about wanting to be with us in school or anywhere else for that matter.)

Certainly, Elizabeth and Nettie and Ernest and Linda and all, you goals were clear to you, at least (not that you encouraged any misunderstanding in the last 53 years about them - as I said, you, or at least your images, were played). Elizabeth, we knew – we always knew – that our asking you to suffer was not just so you could walk down the streets just to pick up on all that white goodness that would supposedly make you Free, White and 21 (except with beautiful brown skin and a hell of a taste in sunglasses.) We knew there was very little goodness to be had, not unless THEY felt like it. Hell – YOU knew. You knew WHY it mattered. Indeed you knew the ONLY reason it mattered, which we in shaming your memory for the last 53 years chasing white liberal pipe dreams and revisionist interpretations of history forgot:

Even though we were a working-class family I'd always been told that I ought to, should, and would go to college. And, in a segregated environment I knew that ... what was available to white students was more than, and better than what was available in a Negro school.

See, the dual school system, was never, it was separate, but it was never equal.

In other words, there were no “I Have a Dream” rose-colored glasses of racial brotherhood steeling you against the hate that came your way when you went to Central High. That was not even the issue. It was not the issue for Melba, either. Instead the prize your eyes were keeping on was clear – at least before revisionist history got done with y’all:

But there has been lots of misunderstanding about why we went to Central High School. Let me be clear: We didn't go to Central to "integrate." We didn't go to Central to sit beside white people, as if they had some magic dust or something. I would not risk my life to sit next to white people. No, no, no, no. . . . Let's get real here. Integration is just a lightly concocted word for "share the wealth"; access to the pie; getting a slice of the American dream. Equal opportunity. We understood Rhodes scholarships, new equipment, wanting to lead better lives. The nine of us went to Central because we wanted to share in that. We also wanted to go to the best colleges, get the best jobs. We risked our lives for access to opportunity, to jobs. We had no illusions that sitting next to white people would lead to better lives.

Even Linda and Cheryl knew that, and acknowledge it even though it was their family's fight that paved the way for you to take that infamous, brutal, violent trip to your first day of school at Central High in Little Rock.

None of the other Little Rock Nine have claimed anything else motivated them, either.

So, you suffered, because it was worth it to you to have a fair shot that your Black skin would have otherwise denied you. And we suffered with you. But only you suffered as only the warrior suffers. Even though you were weary – and prayed to just be a normal person as Melba once prayed in her diaries:

Please God, let me learn how to stop being a warrior. Sometimes, I just need to be a girl.

Yet despite your own personal struggle to further your personal goals, and your parents' goals, you and especially your images and your struggles were hijacked and used as American propaganda - starting with its own citizens. They became the tool through which America filled a pressing need -- and it was not to see you obtain an equal education. Instead, depending on your viewpoint, Brown and your fight for a decent education (1) fulfilled the political need for the United States to defuse the increasing international identification of the US as a hypocrite and racial colonialist power by its World War II and Cold War enemies because of its fierce insistence on racial segregation, as the US tacitly admitted in its amicus brief filed in Brown, or (b) reinforced white supremacist thinking in the 1950s, which could not accept someone else actually coming first in terms of priorities and which was prepared to tear the nation apart if it didn't get its way on this issue.

Because you see, it is really they who are the victims of integration and racism.

Didn't you know? Just ask your friend, and former foul-mouthed tormentor (as shown above) Hazel Bryan Massery.

I know, I know – Hazel Massery said she was sorry, for cussing you. I know she’s the only one that ever did. And I know she’s your friend now. But she should have been sorry. She should have had her foul mouth slapped where she stood, as your mama would have almost certainly done yours had the situation been reversed. I hope the image of what she admitted was a mindless unthinking hate captured in pictures haunts her until the day she dies. I know you said you don’t hate her. I do. As I hate all that type. All those that expect us to feel sorry for them when they are forced by the law to do the right thing by us collectively that they were not persuaded to do by any sense of fairness or obligation as a white citizen still benefitting handsomely each and every day from the invisible knapsack of white privilege. And, adding insult to injury, always expect us to forgive them that they can’t just once let our needs come before one of theirs. All that type of folk. That type like Hazel Massery, who expects forgiveness because she was "just a kid" and her visibly violent diatribe in your direction was just her "[going] with the crowd" since she "wasn't really" following you while she yelling and hating on you. Those like James Eison who (unlike your friend Hazel) to this day refuses to apologize for what went on at Central High – who insists that he is the victim, just as much as you were, because he has lived his life being considered a bad person for what he did when you came to Central High. He claims that desegregation “hurt and scared” him, even though he and his friends walked out of school and masturbated their young injured white manhood by burning a nigger in effigy just because you were going to be at his white school now. That type, the type who insists that, of course, today they’d NEVER say those terrible things. Do those terrible things. Today.

Yet none of them other than Hazel have ever stepped forward to say "I'm Sorry." Which tells you all you need to know about what they consider to be most important - their need not to feel guilty.

But it's not just the ones who tormented you, and the other Little Rock Nine, and Linda Brown. It's those like Cheryl Hopwood, who could handle (since she never bitched about it and her lawyers and the courts didn’t either) that 140 white students were admitted into the University of Texas Law School with grades and test scores worse than hers, but could not handle that 63 Black and Latino students were, too. Woe betide Ms. Hopwood, wounded beyond belief at the very idea that any darkies like us could secure a place at University of Texas Law School before SHE did (unless another white person with lesser qualifications wanted it; that appeared to have been perfectly OK with both her and the Supreme Court.) That the Black and Latino students who were admitted ahead of her were from elite undergraduate institutions and Ms. Hopwood's application lost points under the school’s scoring rubric because she’d gone to community college before transferring to graduate a state school? It did not matter, not to the Court. Any racial consideration in dividing the spoils of access to law school education was wrong if it left any possibility that she had to sacrifice by going to her second choice school (not that she actually proved that she had sacrificed anything, since the courts never did ask her to explain why she should win in light of those 140 other white folks, and the media didn’t either.) Hopwood never did grant an interview to explain her own views, but everyone who spoke for her made a point of highlighting that she was just misunderstood – and she definitely wasn’t a racist: all she was trying to ensure by bringing the case destroying (temporarily) affirmative action in higher education was fairness. She was herself just another victim of racism. Just like you.

And the Courts loved her, at least until another white victim, Jennifer Gratz, came along and then another, Barbara Grutter. Although Barbara Grutter wisely keeps her counsel on concepts like historical discrimination and how it might legitimately affect a school's duty in connection with admissions, young Jennifer (who sued when she was waitlisted at the University of Michigan) suffers no such modesty. Indeed, she wants everyone to know that she too was hurt over affirmative action - except that her pain is more over the harm we supposedly suffered than anything for herself:

I think it's a shame that the university looks at minority students and basically tells them that they are inferior and need these points to be accepted.

So, it really wasn’t Jennifer that felt the Blacks who might have been admitted to University of Michigan with "lesser statistics" ahead of her were inferior (begs the question of why she sued, doesn't it Elizabeth?) -- it was the school, because it didn't admit her in their place unconditionally solely because of her "better statistics." And Jennifer wants us to know that the hurt she feels for us is very real, grounded in real injury:

Gratz: Had I been on Ann Arbor campus, I would have had the opportunity to interview and possibly internship or receive jobs with companies around the country and even possibly around the world. It’s very difficult to say exactly how people are harmed by this, only we know that our lives would be different had we had a fair chance and that opportunity.

That’s mighty white of her, don’t you think, Elizabeth? Saying that she doesn’t know how "people" are hurt, but she just knows that "they" are? At least Barbara Grutter doesn't say much. But then again, she's really no better than Ms. Gratz, despite her comparative silence. After all, 16 whites with inferior point totals to Barbara Grutter's were admitted to University of Michigan Law School her year but the mere possibility that her spot might have gone to an “unqualified” Black or Latino wounded her enough to drive her straight to the courthouse. It just was not fair, because we're supposed to be "colorblind". It, no doubt, hurt, to learn that the world wasn't. Indeed, she was so hurt that after losing at the Supreme Court, she ultimately successfully joined forces with Jennifer Gratz to campaign for Proposition 2's constitutional amendment eliminating all affirmative action in the state of Michigan, just to ensure that no poor white woman (or man either, for that matter) will feel such hurt being asked to step aside to level the playing field for a Black person ever, ever, again.

(Of course, both Grutter and Gratz were so hurt that they also advocated for Amendment 2 despite the “acceptable gender discrimination exception” – something that I’m sure their sisters who had to sue for jobs in the police and fire departments for decades understood completely.)

I hate that type, the Hopwoods and the Grutters and Gratz's and the type that went to court in Parents Involved and Meredith. I hate that type because it is that type – the ones that believe that their minor inconveniences and discomforts that might accrue to accomodating our need for a fair shake, and our people's need, are of equal constitutional and moral value to our hundreds’ year struggle for equality in the country we built – that led to Thursday’s decision. I hate them because it is this type that ultimately persuaded the courts to backpedal almost immediately from the promise of Brown, in a way that the Stormfronts and John Birchers and KKKers never could, their obvious insane race hatred and history of racial violence leaving a stench a mile wide around any possible claim that their fierce opposition to race-conscious strategies to remedy historical discrimination are all really just about the dream of "being judged by the content of one's character."

But I wasn't writing you to talk about those folks. I was writing to you talking about Brown.

As I said above, with the pressures of the Cold War and America's ascension, it could not be seen as a hypocrite on the issue of tyranny, and the international rhetoric was clear that it was vulnerable politically in that sense. Thus, segregation became "un-American", through the vehicle of a 9-0 decision in Brown v. Board of Education. And remained so until, at least, until Thursday, June 28, 2007.

The problem was, and always has been, that segregation isn't really un-American. On the contrary, it's as American as apple pie, and nothing in Brown changed that. At least not in real life, where we and the other hundreds of millions are born, live, eat, play pray, and die. Each day the majority in this country continues to prove its basic agreement with George Wallace's insistent battle cry for America: Segregation Today....Segregation Tomorrow.....Segregation Forever!

They just don't like to talk about it. And definitely not to actually do anything about it. Unless it doesn't cost them anything, that is.

Which is why, early on, many learned people tried to warn us not to put too much stake in Brown and, indeed, some considered it a distraction from the larger goals of our equality because Brown itself could not legislate what really needed to be changed: the hearts, mind and morality of those in the majority, when it came down to truly sharing the fruits of America with their former slave class.

There was an old joke that says "some people go under water as a dry devil and come up a wet devil." The water did nothing to change the soul. The same rang true for white racists who had maintained a racist system of segregated schools. Brown vs. Board of Education did nothing to change their hearts or souls. One day they were openly segregated racists, and the day after Brown vs. Board of Education, they were, theoretically, integrated racists, and they spent their days and nights trying to figure ways to maintain the basis of racism and white superiority in America. Today that work has developed things like vouchers to help maintain segregated schools at the expense of public schools.

The purpose of Brown vs. Board of Education was very simple. Black America knew that the best educational resources were allocated and placed in the schools where the white kids were. To get these resources for Black kids we needed to get the Black kids into those better equipped schools.

Today nothing has changed.

Similarly, Clayborne Carson, (my Freshman English professor and archivist of the King Papers) said upon the 50th anniversary of Brown:

Few African Americans would wish to return to the pre-Brown world of legally enforced segregation, but in the half century since 1954, only a minority of Americans has experienced the promised land of truly integrated public education. By the mid-1960s, with dual school systems still in place in many areas of the Deep South, and with de facto segregation a recognized reality in urban areas, the limitations of Brown had become evident to many of those who had spearheaded previous civil rights struggles. . . By the late 1960s, growing numbers of black leaders had concluded that improvement of black schools should take priority over school desegregation. In 1967, shortly before the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders warned that the United States was "moving toward two societies, one white, one black—separate and unequal," Martin Luther King Jr. acknowledged the need to refocus attention, at least in the short run, on "schools in ghetto areas." He also insisted that "the drive for immediate improvements in segregated schools should not retard progress toward integrated education later." Even veterans of the NAACP's legal campaign had second thoughts. "Brown has little practical relevance to central city blacks," Constance Baker Motley commented in 1974. "Its psychological and legal relevance has already had its effect.

So it was not to hard for me to conclude (or others just as observant) that Parents Involved was truly the end of Brown v. Board of Education. It was the end because Parents Involved (and the companion Meredith case, at long last gave legal sanction to George Wallace's lifelong dream (at least until he miraculously converted into a member of the Rainbow Coalition on his death bed and called his Black manservant his best friend) that his constitutional rights as a white person included the right to stay the hell away from us and the right to have his wants come ahead of our asserted needs. Certainly, nobody rational concluded that the Court was actually affirming anti-segregation principles - indeed quite a few folks are wracking their brains trying to figure out how one cures racial segregation without actually considering race. For example, I’m not too keen on the legacy of the South, and definitely not Texas (which gave us the gag gift that keeps on giving, Dubbya), especially when it comes to racial issues, but I find it hard not to agree with these sage words editorialized Friday in the Houston Chronicle:

In equating the efforts of school districts in Seattle and Louisville, Ky., to diversify their classrooms with the Jim Crow racist systems of the old South, the court has miscast those trying to right historic wrongs in the role of those who created the injustices. . . For the court's majority to claim that it is following the spirit of the Brown decision in invalidating the Seattle and Louisville plans — and hundreds of others across the nation — is to mistake the cure for the disease. Just as race was taken into account in ordering the desegregation of the nation's schools that had deprived so many children of equal rights, so it remains one of a number of factors educators must consider in doing their best to prevent that sorry history from ever repeating itself.

It's enough to make your head hurt.

But, it has been no secret, at least not to lawyers working in the area of race and the law, that Brown was not only dying as it no longer served its purposes (which had little or nothing to do with ensuring our equality), but that it's very language could ultimately would be one of the mechanisms used to enshrine de facto segregation. Alan Freeman tried to warn us, as early as 1978 post-Bakke, in his seminal work Legitimizing Racial Discrimination through Anti-Discrimination Law: A Critical Review of Supreme Court Doctrine, 62 Minn. L. Rev. 1049 (1978) (an article that, strangely, despite its citation thousands of times by legal scholars in the last 29 years it is impossible to find excerpts and quotes from on the Internet *and* impossible to find the full piece on either Lexis and Westlaw as well; thank God I still have my copy from Advanced Con Law). He tried to show us, using language from the precedents themselves, that the Supreme Court’s legacy of anti-discrimination cases was to be systematically moving the courts in the direction of securing, not eliminating, racial discrimination as a hallmark of jurisprudence, under the presumption of legal "colorblindness" unless someone could be clearly deemed to be "at fault" for a racially disparate outcome; what Professor Freeman referred to as the law enshrining the "the perpetrator perspective" on discrimination into law, instead of the more empathic perspective necessary to actually protect its victims.

Although this note to you, Minnejean and Ernest and Linda and Sadie and Elizabeth, is a note of apology, and not an explication of the legal analysis that leads me to such a grim conclusion (I only have 10,000 words, after all) anyone who has studied the anti-discrimination jurisprudence of the United States Supreme Court, and each of the decisions that are at the core of it (from Brown I and Brown II to Sweatt to Fullilove to Bakke, to Adarand, Croson, Swann, Wygant, Milligan and McLauren, Freeman and Grutter) reaches that grim conclusion nonetheless. Thus, we owe thanks to the late Professor Freeman who called the ultimate endgame of cases like Brown -- 37 years ago - when he said that the law's concern with the perpetrator perspective when it came to race would effectively guarantee that racism would continue. And tried to tell us why, in advance.

As another of those law professors who tried to warn us that Brown was dying, if not already dead, and tell us why long before this past Thursday, Professor Derrick Bell also deserves our special thanks. Frankly, had I not read his works over the years since I started studying law, I might be feeling the same confusion as my DAH (who upon hearing the news Thursday that Brown had been dealt a fatal blow kept asking “Why would they [the Court] even feel the need to do that?” Yes, Elizabeth, they knew about Brown all the way Down Under.) But the words of Derrick Bell’s about Brown in Silent Covenants: Brown v. Board of Education and the Unfulfilled Hopes for Racial Reform comforted me on Thursday, and reassured me through the sense of disorientation and confusion that I felt, even knowing in advance with virtual certainty what was going to happen when the Supreme Court finally spoke. They consoled me because they helped me understand how Brown, like the beliefs of Dr. King, had been coopted and repackaged and sold to the masses after the fact as something far more palatable to whites and powerful in terms of anti-racist struggle than it ever was allowed to actually be in real life:

Deserved or not, this nation has managed to find a place in its pantheon of heroes for Brown v. Board of Education, a decision which promised much and of which, I am convinced, the Supreme Court expected much. I have tried to explain here why I believe it fell so far short of its goals. In that I am aided by the Rev. Peter Gomes, minister of the Memorial Church at Harvard University. Gomes wrote about Martin Luther King, Jr. in terms that apply equally to the Brown decision:In death he was able to the claim the loyalty denied him in life, for it is far easier to honor the dead than to follow the living, and so we take the dead to our bosoms, for there they can no longer do any harm; and we can translate a living, breathing, both noble and fallible human being into a heroic impotence, satisfying our need to both admire and be protected from something larger than ourselves.

Gomes's words give meaning to the event described at the beginning of this book, when, at a Yale University commencement, applause followed the reminder that the Brown decision would soon be fifty years old. It was a dramatic instance of how readily this society assimilates the myriad manifestations of black protest and achievement. In that process, the continuing devastation of racial discrimination is minimized, even ignored, while we in the civil rights movement who gained some renown as we labored to end those injustices are conveniently converted into cultural reinforcements of the racial status quo. We become irrefutable proof that black people can make it in America through work and sacrifice.

Work and sacrifice, as important as they are, have never been sufficient to gain blacks more than grudging acceptance as individuals. They seldom enjoy the presumption of regularity, the sense that they belong or are competent, which whites may take for granted. Of course, at some point on the ladder of achievement, blacks are no longer deemed black by those whites who know them. We are told point-blank that we are “different.” Sadly, but understandably, there are black people who view such statements as compliments.

The psychic damage done by unofficial long-term exclusion is impossible to measure. None of us are immune, not even those whose fight to end racism or try hard to understand, describe and record it. Boston College law professor Anthony Farley, who views the quest for racial equality as an almost romantic longing for acceptance, writes:Everybody at some level believes in it. It’s a deeply seductive image. The image that all we want, as oppressed people, is an image of our masters finally loving us and recognizing our humanity. It is this image that keeps prostitutes with their pimps, the colonized with their colonizers, and battered women with their batterers. Everybody dreams of one day being safe.

There is no place safer for us than in education. As your mamas told you, and my mama told me, and all the Black mamas and daddies I know told their youth, education was a must, because education was the one thing that "they" (and we know who "they" are/were) could never take away from you. I never really understood what it meant until about 10 years ago, when I started learning about our people's efforts to become educated when folks actually were trying to take it from us.

And there, my dear Elizabeth, Nettie, Thelma, Gloria, Minnijean and Nikki, and all the brothers, too, is the good news I was telling you about. The good news lies in your own original reasons for struggle - and our people's renewed eyes on THAT prize. The good news is that we have never needed integration to secure our children's education or flower their extraordinary gifts. Instead, the history before Brown was quite remarkable: left to our own education, we educated ourselves. And we did it WELL. Indeed, it has been recognized for more than 100 years that our greatest achievements in education came largely from us doing it for ourselves. Perhaps it was because, in the end, of the intractible nature of white supremacy in America itself, and its impact on the souls of Black folk when we left our training and education to those in the majority. After all, as the Father of Black History wrote nearly 75 years ago:

When you control a man's thinking you do not have to worry about his actions. You do not have to tell him not to stand here or go yonder. He will find his 'proper place' and will stay in it. You do not need to send him to the back door. He will go without being told. In fact, if there is no back door, he will cut one for his special benefit. His education makes it necessary.

Carter G. Woodson, Miseducation of the Negro (1933)

Similarly, W.E.B. Dubois was one of the earliest who asserted that we can and must educate ourselves, in his 1902 editorial On the Training of Black Men:

. . . . [W]hen turning our eyes from the temporary and the contingent in the Negro problem to the broader question of the permanent uplifting and civilization of black men in America, we have a right to inquire, as this enthusiasm for material advancement mounts to its height, if after all the industrial school is the final and sufficient answer in the training of the Negro race . . . The tendency is here born of slavery and quickened to renewed life by the crazy imperialism of the day, to regard human beings as among the material resources of a land to be trained with an eye single to future dividends. Race prejudices, which keep brown and black men in their "places," we are coming to regard as useful allies with such a theory, no matter how much they may dull the ambition and sicken the hearts of struggling human beings. And above all, we daily hear that an education that encourages aspiration, that sets the loftiest of ideals and seeks as an end culture and character than bread- winning, is the privilege of white men and the danger and delusion of black.

Especially has criticism been directed against the former educational efforts to aid the Negro. . . . Soothly we have been told that first industrial and manual training should have taught the Negro to work, then simple schools should have taught him to read and write, and finally, after years, high and normal schools could have completed the system, as intelligence and wealth demanded.

That a system logically so complete was historically impossible, it needs but a little thought to prove. . . [T]he mass of the freedmen at the end of the war lacked the intelligence so necessary to modern workingmen. They must first have the common school to teach them to read, write, and cipher. The white teachers who flocked South went to establish such a common school system. . . . But they faced, as all men since them have faced, that central paradox of the South, the social separation of the races. . . . Thus, then and now, there stand in the South two separate worlds. . . [and] the separation is so thorough and deep, that it absolutely precludes for the present between the races anything like that sympathetic and effective group training and leadership of the one by the other, such as the American Negro and all backward peoples must have for effectual progress.

This the missionaries of '68 soon saw; and if effective industrial and trade schools were impractical before the establishment of a common school system, just as certainly no adequate common schools could be founded until there were teachers to teach them. Southern whites would not teach them; Northern whites in sufficient numbers could not be had. If the Negro was to learn, he must teach himself, and the most effective help that could be given him was the establishment of schools to train Negro teachers. This conclusion was slowly but surely reached by every student of the situation until simultaneously, in widely separated regions, without consultation or systematic plan, there arose a series of institutions designed to furnish teachers for the untaught. Above the sneers of critics at the obvious defects of this procedure must ever stand its one crushing rejoinder: in a single generation they put thirty thousand black teachers in the South; they wiped out the illiteracy of the majority of the black people of the land, and they made Tuskegee possible.

In the end, now, it is those of us who followed in your brave footsteps – sometimes by choice, sometimes at the insistence of parents who simply would accept nothing less from us than the best – to carry the work forward again of securing a quality education for our youth despite the ten steps back towards Plessy which the disingenuous reasoning and rhetorical parth the Roberts Court in Parents Involved has taken. But the truly good news is that we don't have to start from scratch. The formula to help our children succeed despite a hostile, racist world has been there waiting us to find it again since we abandoned it for the promise of integration in 1954:

Teach them ourselves. In our own schools.

Some of us have been calling for this approach for years, in both scholarly article and public manifesto, and renewed the calls during the 50th anniversary of Brown just a few years ago to be about education first, being with white folks later (if ever:)

We will use this hundredth anniversary of Plessy to re-examine and recommit to ending inequality in our schools by any just means necessary. If integration can be achieved in the process, all well and good. However, the focus must be on quality and equality, not on the mere physical presence of both races in one school building.

And so, for at least the last ten years, schools and techniques specifically designed to teach our children as Black people have slowly re-emerged from their dormancy in the 1970's and 1980's and are taking hold in our communities. They are as far flung as the diaspora is within the United States. Some are Afrocentric. Some are religious. Some are collaborations of homeschooling parents. Yet all have one purpose: to provide our children with the quality education that integrated education has failed to provide in a country where, in many areas, resegregation of both students and teachers is a fact of life. Separate schools, and unequal.

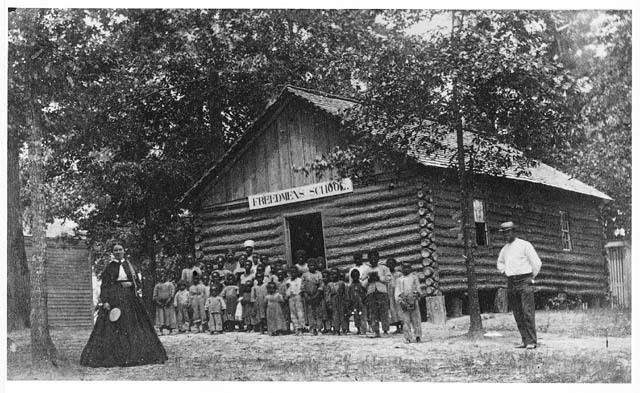

Yet now, we no longer have the promise of Brown and the methods of integration to attack them. So in many ways, we have come full circle. And must begin work again, to educate our own because it is clear that nobody else will. And maybe, this time, if we keep at it until the job is done, we will no longer have to hear the racist tropes and lies about the educability of our children, and the reasons that they do not succeed in education, that were proven wrong nearly 150 years ago yet by the thousands of Freedman’s Schools

and proven wrong again 40 years ago by the Freedom Schools

And no doubt proven wrong again by the newest incarnations, such as the new generation of Freedom Schools today. Take a look at what these schools are doing. These are the future Black leaders that will prove them wrong, yet again:

It is in watching and hearing their joy at learning, when so often all we see and hear is that our children are alienated from learning, that we as Black people should know that everything that has been said since our children’s deteriorating progress in education began post Brown that you know that each and everything theory advanced by whites (liberal *and* conservative) and their right-wing Black collaborators, to explain our children's dying thirst for academic achievement is just flat out wrong, and that any and all solutions that presupposed that there was something wrong with us that kept us from succeeding will be summarily dismissed and become historical dinosaurs in the way that Brown is now destined to become. Perhaps this time, we will shut once and for all the tropes and myths about our people’s intellect and ability to succeed that have gotten in our way – since we still have to be twice as good to get ½ as far – that underlie educational policy today, most of which continue to be uttered by the most well-meaning folks and towards which education has thrown billions has been thrown with almost nothing thrown at those who already knew the way to teach black children. Bullshit myths and slogans and superficial understandings which folks have insisted upon as the reason our children have lost academic ground or are treading water:

Black culture causes parents not to care about their children’s education. Bullshit.

Black culture is “anti-intellectual”. Bullshit.

Black youth believe that trying to get an education is “acting white.” Bullshit.

Bullshit.. And even more Bullshit Hell, even the rabidly conservative Hoover Institute confirmed it was largely Bullshit – except in integrated schools. (And, most egregiously, bullshit initially advanced by an immigrant Black researcher who let his immigrant experiences detract him from the job of looking below the superficial surface of anecdotal statements before taking advancing such a racist hypothesis about a uniquely-Black-American cultural phenomena which he neither experienced as a child or, clearly, bothered to actually interview anybody other than kids about in depth, and being currently spouted as gospel by the only Black man running for president.)

The scary part is that, when it comes to this good news, there is actually a bonus item: on the question of education, going back to our old approach (we'll do it our damned selves) may well finally bridge the communication gap between Black liberals and Black conservatives. Since on the question of our quest for educational equality and opportunity, they appear to be in agreement with the more progressive of us that integration was not the point, is not the point, and shouldn't ever be the point of Brown v. Board of Education.

For example, as I hate to admit it because I don’t agree with most of Juan Williams’ apologist op-ed in Friday's New York Times upon the death knell to Brown, (I suspect some of you wouldn’t agree either) he did make one valid point with which we can all agree:

In 1990, after months of interviews with Justice Thurgood Marshall, who had been the lead lawyer for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense Fund on the Brown case, I sat in his Supreme Court chambers with a final question. Almost 40 years later, was he satisfied with the outcome of the decision? Outside the courthouse, the failing Washington school system was hyper-segregated, with more than 90 percent of its students black and Latino. Schools in the surrounding suburbs, meanwhile, were mostly white and producing some of the top students in the nation.

Had Mr. Marshall, the lawyer, made a mistake by insisting on racial integration instead of improvement in the quality of schools for black children?

His response was that seating black children next to white children in school had never been the point. It had been necessary only because all-white school boards were generously financing schools for white children while leaving black students in overcrowded, decrepit buildings with hand-me-down books and underpaid teachers. He had wanted black children to have the right to attend white schools as a point of leverage over the biased spending patterns of the segregationists who ran schools — both in the 17 states where racially separate schools were required by law and in other states where they were a matter of culture.

If black children had the right to be in schools with white children, Justice Marshall reasoned, then school board officials would have no choice but to equalize spending to protect the interests of their white children.

It is now clear that they have all the choice in the world, now. (Except, of course, the choice to keep their existing race based voluntary desegregation programs, whether or not there is a poor white cherub who complains or not. Justice Roberts and his Court made plain on June 28, 2007, that they have no choice at all.)

Similarly, one of my least favorite Black persons on earth is Thomas Sowell. I had the displeasure of personally discussing race matters with once. But only once, thank God. I’m sure he would not remember me (not that he likely remembers all that many black Stanford students period, having being ensconced in the white ivory tower known as HooTow for so long). He’s made a career out of reinforcing for whites in their deep seated need to be absolved from responsibility for any problems faced by Black people. That being said, however, even a broken clock can be right twice a day and, thus, Sowell was right to point to the history of all-Black education in America (Black schools run by Black people to teach Black children) and the law of unintended consequences, - specifically, the fact that upon Brown’s decision to integrate us all on the theory that without integration Black children were doomed, nobody gave a thought to what it would mean to our already existing, already successful, albeit segregated, Black schools and the impact on our children’s educational prospects long-term if they disappeared.

Hell, even Uncle Thomas, for once, pretends to actually care about Black people, in his concurrence in Parents Involved, which rightfully points out in his concurrence (remember what I said about that twice a day correct clock) that the Seattle school district who was defending Parents Involved nonetheless has within it an Afrocentric K-8 school that is producing far more successful Black students, gradewise, than at its average schools. (Of course, Justice Thomas then goes on to gleefully try and wrap himself in the philosophical mantle of late Justice Marshall when it comes to the “Colorblind Constitution”, but that doesn't worry me too much. I figure he has to go to sleep sometime and I know that Thurgood Marshall’s ghost is going to be gunning for him given the disingenuousness of this particular claim.)

Of course, there will always be the naysayers, most sponsored financially by neocon racist think tanks, who get paid to vent their emotional angst about the idea that Black folks’ present collective situation might actually be due to something other than our own dysfunction, “anger” and “culture of poverty”, particularly when Black folks come up with something on their own, and particularly with an Afrocentric perspective that did not first receive the majority’s imprimatur of approval.

But what else is new? Hannah Arendt spoke perhaps most eloquently for them all nearly 50 years ago, post-Brown, in her Reflections on Little Rock, 1957-1959 (1959), in which she claimed that she was only thinking of your hurt feelings and your best interests upon seeing your pictures, Elizabeth, when she asserted an absolute right of free association in America, starting with most critically the freedom *not* to associate, and expressed her solidarity with folks who opposed integration and Brown. Like your former tormenter, later friend, Hazel Massery.

Perhaps Arendt was right (however brutally stated her position was, or however self-serving those arguments were when being advanced by a white woman in 1958): For America, at least, maybe the very survival of the Republic, of the nation, really does demand that it protect the white right Not to associate (even though Arendt claimed it was a right everyone had, Hannah Arendt had not yet evaluated what that really meant in a society where Black survival depends on interacting with whites for just about everything.) It seems, anyhow, not an unfair reading of Thursday's decision, at least in the context of education.

At least, that's what it means so long as we never, ever admit to the truth about our country's racist feelings, ever again. Except in coded words and coded behavior which we all recognize for what it is today, but one day we will forget the origins of. Code which neither the law nor the courts will ever acknowledge for what it really is.

Since as it has not once acknowledged it directly since Brown first became law and the white backlash began 53 years ago.

For that, I'm sorriest of all. Your sacrifices and your parents' belief that all would be well if only you held your head up high while fighting for that in which you believed should not have come to mean, in any one's mind, that your struggles were to ensure protect the right for whites to decide how and when they will interact with us in the educational arena. And yet, in the words of Chief Justice Roberts, that's indeed what Brown v. Board of Education, and thus, the struggle for integrated schools, really stood for. Except that Justice Roberts and four others said that Brown was the struggle for "a colorblind society" in which race could never be taken into account - even to further good, instead of its historic evil.

So, ever in your debt, and knowing that your heads are still held high, even if after Thursday it is likely that you, like millions of us, are no longer even inadvertent slaves to the national delusion of brotherhood through integration (since, after all, you only wanted the equal education to which you were absolutely entitled as American citizens), thank you for fighting, nonetheless. It's up to the rest of us, now, to determine what your legacy will really mean. Once and for all.

Finally, as one of the greatest educators of our people, starting with our women, and one of my personal heroines (despite her idolization of Booker T. Washington), Mary McLeod Bethune, wrote:

If we have the courage and tenacity of our forebears, who stood firmly like a rock against the lash of slavery, we shall find a way to do for our day what they did for theirs.

The drums of Africa beat in my heart. They will not let me rest while there is a single negro boy or girl lacking the opportunity to prove his or her worth.

You had the courage. The tenacity. You stood firmly like rocks at a time when it was clear that those others felt you had no worth, and no value worth educating at a level equal to theirs. Now that we have been told that the national experiment began with our courage will again fade to the urgency of the needs of those who have always believed that their wants were more important than our needs, I pray that we will again find a way to do for our day what you did for yours.

Brown v. Board of Education is dead. Long live Brown.

4 Comments:

my name is neeka sullivan i am the little girl in the picture on the spreme steps of the cout house with my grandmother nettie hunt my grandmother was a very strong women and made sure all of us got a education . this picture makes me proud to be in it for a good thing my grandmother would have been over joyed about it. i see a lot of people have made money on this picture as i remember my grandmother going to the mail box looking for the check the man that took the picture never sent it to her. he promise he would now i show the picture to my grandson who looks like me in the picture i can to reach at 4631 5 street n.w.\washington,d.c.20011 when i first saw the picture i though i was a movie star every smiled when i said it.grandmaneeka@yahoo.com

i dont like u neeka sullivan

ur not really her, iam.

i know

Post a Comment

<< Home